- Home

- Lysley Tenorio

Monstress

Monstress Read online

Monstress

Stories

Lysley Tenorio

Dedication

for my mother,

Estrella Agojo Tenorio

and in memory of my father,

Pioquinto Gahol Tenorio

Contents

Dedication

Monstress

The Brothers

Felix Starro

The View from Culion

Superassassin

Help

Save the I-Hotel

L’amour, CA

Acknowledgments

Praise for Monstress

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Monstress

In 1966, the president of CocoLoco Pictures broke the news to us in English: “As the Americanos say, it is time to listen to the music. Your movies are shit.” He unrolled a poster for The Squid Children of Cebu, our latest picture for the studio. Our names were written in drippy, bloody letters: A Checkers Rosario Film was printed above the title, and my credit was at the bottom. Reva Gogo, it said, as the Squid Mother.

In its first week in release, Squid Children played in just one theater in all of Manila, the midnight show at the Primero. “A place for peasants and whores,” the president said, tearing the poster in half, “and is it true they use a bedsheet for a screen?” Then, speaking in Tagalog, he fired us.

From CocoLoco we walked home, and when we passed the Oasis, one of the English-only movie theaters that had been sprouting up all over Manila, Checkers threw a stone at Doris Day’s face: Send Me No Flowers was playing, and above the box office Doris Day and Rock Hudson traded sexy glances and knowing smiles. “Their fault!” he said, and I understood what he meant: imported Hollywood romance was what Manila moviegoers were paying to see, and Checkers’ low-budget horror could no longer compete. “All that overacting, that corny shit!” But here was the truth: those were the movies I longed for Checkers to make, where men fall in love with women and stay there, and tearful partings are only preludes to tearful reunions. Real life—that’s what I wanted to play, but my only roles were Bat-Winged Pygmy Queen, Werewolf Girl, Two-Headed Bride of Two-Headed Dracula, Squid Mother—all those monstrous girls Checkers dreamed up just for me.

I took the second stone from his hand and put it in my purse. “Time to go home,” I said.

But we did not give up. Checkers shopped his latest (and last) screenplay, Dino-Ladies Get Quezon City, to all the Manila studios, even one in Guam; every answer was no. I auditioned and auditioned, and though casting agents liked my look (one called me a Filipina Sophia Loren), cold readings made me look like an amateur: I shouted dialogue that should have been whispered, and made tears of sorrow look like tears of joy.

For the next three years, this was our life: I worked as a receptionist at a dentist’s office and Checkers lamented. One night, I woke to the sound of thwacking, and I found him drunk on the balcony, cracking open coconuts with a machete. “Was I no good?” he asked, his grunts turning to sniffles. I went to him, rested my head against the back of his neck. “Your chance will come again,” I said. “But it’s time for us to sleep.”

Sometimes, when I play that night over in my head, I give it a new ending: I answer Checkers with the truth, that the most he ever achieved was minor local fame; that his movies were shoddily produced, illogically plotted, clumsily directed. This hurts Checkers—it hurts me, too—but the next morning we go on with our life, and I marvel at the possibilities: we might have married, there could have been children. We would still be together, and we wouldn’t have needed Gaz Gazman, that Saturday morning in January of ’70, when he rang our doorbell.

“Who are you?” I asked. Through the peephole I saw a stranger in a safari hat wipe his feet on our doormat as though we had already welcomed him.

“The name’s Gazman. From Hollywood, USA. I’m here for a Checkers”—he looked at the name written on his palm—“Rosario.”

I put my hand on the doorknob, made sure it was locked. “What do you want?”

He leaned into the peephole, his smile so big I caught the glint of a shiny gold crown on a back tooth. “His monsters,” he said.

From the bedroom I heard Checkers start his day the usual way, with a phlegmy cough from the previous night’s bourbon. I went to him. “Someone is here,” I said, poking his shoulder. “From Hollywood.”

He lifted his head.

I returned to the front door. I didn’t want to, but I did. For Checkers. I unlocked the lock and let Gaz Gazman in.

I led him to the kitchen, offered him a plate of Ritz crackers and a square of margarine. I stood by the sink, watching him as he ate: his shirt and shorts were covered with palm trees, and his purple sandals clashed with the orange lenses of his sunglasses. A large canvas bag was on the floor beside him, and his hat was still on.

Checkers stepped into the kitchen. “The great Checkers Rosario,” Gaz said.

Checkers stared at Gaz with bloodshot eyes. “Used to be,” he said, then sat down.

Gaz explained himself: he was in Manila visiting an ex-girlfriend, a makeup artist for CocoLoco. He had toured the studio, gone through their vaults, and found copies of Checkers’ movies. “I watched them all, and I thought, Jackpot—Eureka! This is the real deal. They said if I wanted to use them, I should find you.” He pulled four canisters of film from his canvas bag and stacked them on the table. “And now you’re found.”

Checkers took the reels from the canisters. I could hear him whisper their titles like the names of women he once loved and still did—The Creature in the Cane, Cathedral of Dread, DraculaDracula, The House on Dead Filipino Road. “Use them,” he said. “What for?”

“Three words,” Gaz said. “Motion. Picture. History.” He got up, circled the table as he explained his movie: en route to Earth from a distant star system, the crew of the Valedictorian crash-lands on a hostile planet inhabited by bat-winged pygmies, lobster-clawed cannibals, two-headed vampires. “That’s where your stuff comes in. I’m going to splice your movies with mine.” He went on about the mixing-up of genres, chop-suey cinema, bringing together East and West. “We’d be the ambassadors of international film!”

“What’s your thinking on this?” Checkers asked me in Tagalog. “Is this man serious? Is he just an American fool?”

“Ask how much he’ll pay,” I said, “get twenty percent more, give him the movies, and show him to the door.”

“All our hard work for a few pesos?” Checkers looked at me as though I’d slapped him. “That’s their worth to you?” He asked if I’d forgotten the ten-star reviews, the long lines on opening night, but I didn’t want to hear about it, not anymore, so I reminded him about the life we’d been living the last three years—how I sat day after day in an un-air-conditioned dentist’s office, staring at a phone that never rang, while he slept through hangovers into the late afternoon, only to reminisce about our CocoLoco days throughout the night. “Take the money,” I said, “and let’s be done with this.”

“I come in peace!” Gaz said. “Don’t fight because of me.”

I switched back to English. “We are discussing, not fighting. We don’t have lawyers or agents to counsel us over these matters. There is corruption and dishonesty in the movie business here in Manila. It’s not like in Hollywood.”

“But I’m one of the good guys,” Gaz said, and to prove it, he made us an offer: “Come to America. Just for a week. You can see a rough cut, visit the set, meet the cast. Plenty of room at my pad. I’ll even take the couch. And if you don’t like what you see, I’ll reimburse you the airfare and you won’t ever hear from me again.”

Then Checkers said, “Reva will come too.”

I shook

my head. “This is your business.” I spoke in English, so that Gaz would understand me too. “The two of you. Not the three of us.”

“But I need you,” Checkers said. He came to me and held my face, then kissed me just above my nose.

Gaz winked at me. “How can you say no to that?”

There was a smudge of gray just above Checkers’ lip, like dried-up toothpaste or cigarette ash. I licked my thumb, rubbed it away. His shirt was misbuttoned at the top, there were patches of stubble he missed when he shaved, and his Elvis-style pompadour showed more gray than I’d realized was there.

“I can’t,” I told Gaz.

“Someone in America is dead.” This was the lie I told the dentist when I asked for a week off from work. “Someone close to me.” It was easy to say—I told him over the phone—but part of me hoped he would deny my request. If I had to stay, maybe Checkers would, too. But the dentist said my presence made no difference, that no one could afford dental work these days, so maybe we were all better off if we simply went away. He wished me a happy trip and hung up before I could say thank you.

We left Monday morning, and our flight to California felt like backwards travel through time. In Manila it was night but outside the plane the sky was packed with clouds so white they looked fake, like the clouds painted on the cinderblock walls of the Primero. Checkers and I began our courtship there, thirteen years before. I was sixteen, he was twenty-two, and every Saturday night we held hands in the second row at the midnight double creature feature. Checkers would marvel at what he called “the beauty of the beast,” confirming the expert craftsmanship of a well-made monster with a quiet “Yes” (he gave a standing ovation to the Creature from the Black Lagoon) and let out exasperated sighs for the lesser ones. But I preferred the monster that could be tamed. Like Fay Wray, I wanted to lie on the leathery palm of my gorilla suitor, soothe his rage with my calming, loving gaze. “You’ll be on-screen one day,” Checkers said. “I’ll put you there. Just keep faith in me.”

So I did. After high school, I moved in with Checkers, took odd jobs sewing and cleaning while he worked on his treatment for The Creature in the Cane. The night CocoLoco Pictures bought it, Checkers gave me a white box tied with pink ribbon. “Wear this,” he whispered. “For me.” I expected a nightgown with a broken strap and tattered neckline—standard attire for a woman in peril—but when I opened it I found a pair of wolf ears, a rubber forehead covered with boils, several plastic eyeballs. “You will be the Creature,” he said, near tears and smiling. “You.”

The night we started filming, as I rubber-glued eyeballs to my face, I told myself this was a first step, that even great actresses have unglamorous starts. I told myself this again the night of the premiere, when audiences cheered wildly as a dozen sugarcane farmers descended upon the Creature with sticks and buckets of holy water. This is only the beginning—I repeated, like a prayer, through all the films I did for Checkers.

For nearly the entire flight over, Checkers slept with his head resting on my chest, but our landing was so rough and jolting that he woke in a panic, and his head slammed hard against my chin. “We’re here?” he said, breathing heavy. “Have we finally arrived?” I rubbed the back of his neck to calm him. But my lip was bleeding. I could taste it.

Gaz didn’t live in Hollywood. He lived east of it, in Los Feliz, in a gray building called the Paradise. “This is it,” he said, unlocking the door, “the home of Gaz Gazman and DoubleG Productions.” It was a tiny apartment furnished with a sinking couch and a pair of yellow beanbags, and the offices of DoubleG Productions were a walk-in closet with a metal desk crammed inside, a telephone and a student film trophy—second place—on top of it. A junior college diploma hung above the fake fireplace, and it was then that I learned Gaz Gazman was not his real name. “Who the hay wants to see a movie by Gazwick Goosmahn? But Gaz Gazman”—he snapped twice—“that’s a director’s name.”

“It’s the same with me!” Checkers said. “My real name? Chekiquinto. Can you believe?” He shook his head and laughed. “Chekiquinto. My gosh!”

“Horrible!” Gaz laughed along. “And you? Is Reva Gogo for real?” He said it like he already knew that it wasn’t. My real name was Revanena Magogolang, but Checkers thought all the repetitive syllables made my name sound like a tongue twister, so right before The Creature in the Cane was released, he de-clunked it down to its smoothest sound. And Reva Gogo, my credit read, as the Creature.

I took Checkers’ hand and made him sit with me on a beanbag. “Show us your movie,” I said. The sooner we saw Gaz’s clips, I thought, the sooner we could get our money and fly home.

Gaz wheeled in a film projector from his bedroom, loaded a 16 millimeter reel, then hung a white bedsheet on the wall. “There are rough spots,” he said, “but I think you’ll like what you see.” He drew the curtains, turned off the lights, filled a bowl with pretzels, then showed us the footage he’d completed so far.

The film opened with a view of Earth from outer space, and a voice (Gaz’s) began: “The year is 1999. The world and all its good citizens have never been better. World peace has been achieved, no child goes hungry, disease has been gotten rid of. Man is free to contemplate the human condition, and, more importantly, colonize outer space.” Entering the picture was a bottle-shaped spaceship, THE VALEDICTORIAN glittering in blue letters along its hull. “There she is,” Gaz whispered, “the smartest ship in the fleet.” A whistle blew, and then a weird, psychedelic montage of oddly angled stills began: there was Captain Vance Banner, the square-jawed fearless leader; Ace Trevor, the hotheaded helmsman; the Intelli-Bot 4-26-35 (“My birthday,” Gaz said); and finally Lorena Valdez, the raven-haired, olive-skinned meteor scientist. “Eyes darker than the cosmic void, lips redder than human blood,” Gaz quoted from his script.

Gaz loaded a second reel, quick scenes of the actors running in a nearby canyon, which would be the planet inhabited by Checkers’ monsters. “That’s where I’ll splice your footage in,” Gaz said. The canyon scenes were composed of reaction shots, extreme close-ups of the actors shouting, “Look out!” “Duck, Captain, duck!” and “They’re hideous!” “I had them take expressions lessons in West Hollywood.” Gaz said. “They’ve definitely done their homework.”

I looked at Checkers. There were pretzel crumbs on the corner of his mouth, but when I tried to wipe them off he brushed my hand away. “Ssshh,” he said. His face glowed blue from the movie on the wall, as it once did back in the CocoLoco editing room, late at night after a long day’s shoot. I would end up asleep on the floor, and when I woke the next morning he’d still be in his chair, struggling to make every scene as perfect as it could be.

Gaz turned off the projector. “And that’s just the beginning.” He smiled. “So, are we in?”

Even before Gaz turned on the lights, Checkers was on his feet. “Let’s do it,” he said. His breathing was heavy and fast, almost desperate, and his forehead was drippy with sweat. “I’m ready,” he said, “we’re in.”

It was still early evening, and Gaz suggested we drive to the set. “MGM?” Checkers guessed. “Twentieth Century-Fox?”

“My mom’s basement in Pasadena,” Gaz answered.

Freeway traffic was slow; I fell asleep in the backseat, and when I woke we were in front of Gaz’s mother’s house. It was an old, peeling Victorian with a shingled roof that had almost no shingles left, and the shutters dangled from the uppermost windows, like limbs attached to a body by one last vein. That house would have been Checkers’ dream set. We’d had to make do with tin-roofed shacks and three-walled huts in shantytowns far beyond Manila, where we paid impoverished locals with cigarettes and sacks of rice to play our victims for a day. “If we’d had something like this to work with,” Checkers said, “life back home would still be good.”

The basement was like an underground studio set, sectioned off by plywood partitions and cardboard walls: each room was a different section of The Valedictorian—the bridge, the science lab, the wea

pons bay, the space sauna. We hadn’t been on a set since Squid Children five years before, but Checkers made himself at home, examining each room from different angles, as though he were behind a camera, filming right then.

I wandered off alone. “Explore all you want, but don’t touch anything,” Gaz said. But I didn’t need to touch anything to know its cheapness: the helm was made of Styrofoam and cardboard, painted to look like steel; the main computer was a reconfigured pinball machine; the Intelli-Bot 4-26-35 was an upside-down fishbowl painted gold atop a small TV set, and its bottom half was a vacuum cleaner on wheels. But I was used to this lack of marvelousness, because Checkers worked this way too, attempting magic from junk: wet toilet tissue shaped like fangs was good enough for a wolf-man or vampire, and our ghosts were just bedsheets. For the Squid Children, Checkers found a box of fireman’s rubber boots, glued homemade tentacles (segments of rubber hose affixed with suction cups) on them, then made his tiny nephews and nieces wear them on their heads. “On film,” Checkers used to say, “everything looks real.”

I found Checkers and Gaz in the space lab, the contract between them: Gaz would pay twenty-five hundred dollars up front, then pay five percent of the profits. “Jackpot-Eureka!” Checkers said after he signed, though neither of us knew how much that would be worth back home.

Gaz and Checkers wanted to celebrate, so we went from bar to bar on Hollywood Boulevard, then strolled along the Walk of Fame. “A trio of visionaries should have the stars at their feet, right, Chex?” Gaz said. Checkers nodded, zigzagging down the street. For so long, Checkers had resented Hollywood, convinced it was American movies that drove us out of the business. Now, here he was, lolling about in enemy territory, drunk from beer, bourbon, and all the inspiration surrounding him—the Hollywood Wax Museum, Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, even the life-size celebrity cutouts in storefront windows. I tried keeping up, making sure he didn’t fall.

Hours later, Checkers and I made love on Gaz’s couch. At first I told him we shouldn’t, not there in a stranger’s home. “He’s so drunk he’ll never wake up,” Checkers assured me. He nibbled my neck and nuzzled my breasts, let out a low guttural growl. “Gently,” I said, running my fingers through his pompadour, “softly.” He obeyed. I knew Checkers was drunk, but this was how I wanted us to finish the day: it was the longest of our lives, thirty-seven hours since we left Manila. So I gave myself up to this moment when we could finally slow down, and I imagined us as Deborah Kerr and Burt Lancaster in From Here to Eternity.

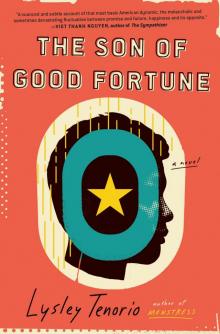

The Son of Good Fortune

The Son of Good Fortune Monstress

Monstress